INDEX

WHAT ARE SPIDER VEINS

SCLEROTHERAPY FOR SPIDER VEINS

WELCOME to this in-depth article about treating spider veins with SCLEROTHERAPY. If you’re here, you like to be well informed before starting a treatment.

In this article we focus specifically on SCLEROTHERAPY FOR SPIDER VEINS. Sclerotherapy can also be used for other problems (varicose veins, vascular malformations, venous ulcers, etc.), but that lies outside the scope of this article. Here you’ll find information exclusively about treating spider veins with sclerotherapy.

WHAT ARE SPIDER VEINS?

Put simply, spider veins are tiny skin capillaries that have dilated enough to become visible.

Think of the skin as a giant “radiator” made up of millions of microscopic, interconnected capillaries. A small number of these dilate until they are visible—those are spider veins.

Spider veins are a very common reason to seek medical advice and are often surrounded by misconceptions. They are small superficial blood vessels in the skin; they vary in shape and length, can appear singly or in clusters (hence the “spider’s web” look; others appear tree-like). They are always under 2 mm in diameter.

They arise due to dilation of the intra-dermal capillaries (note: NOT the superficial venous system beneath the skin), which is why they are so fine.

Why do they appear?

Truthfully, we know relatively little with certainty. Much has been written, but many claims lack solid evidence. That said, a couple of points seem clear, and a few more are logical or probable:

- Genetic factor. Although specific genes haven’t been identified yet, there appears to be a predisposition to capillary fragility. By this we mean that the wall of some tiny skin capillaries is slightly weaker than normal, so they dilate more easily and become visible. This may coexist with features like thin skin (not always) or easy bruising after minor knocks—or even spontaneously. Being a genetic feature (the individual was born with it), there is nothing we can do to modify it (at least up until nowadays). Being genetic means you’re born with it; it does not necessarily mean it’s hereditary.

- Hormonal factor. Female hormones act on these capillary walls in people with the genetic predisposition and cause dilation. This explains why women are more likely than men to have spider veins, why they often increase during pregnancy, and why oral contraceptives or other hormone therapies may trigger them in predisposed people. Steroids (notably corticosteroids) may also play a role.

- Overweight. Increased fat in the legs can make subcutaneous tissues laxer and less supportive, favouring capillary dilation.

- Age. As with many tissues and organs, skin becomes more fragile with age, and its capillaries likely do too.

Although many sources link spider veins with varicose veins, this is generally not true: many people with varicose veins do not have spider veins and vice versa. However, it is essential to perform a duplex ultrasound before any treatment because, if someone has both spider veins and venous insufficiency/varicose veins (visible or not), treating the spider veins first may be ineffective, carry a higher risk of adverse events, or even be unsafe, if the larger veins are not addressed beforehand.

What types of spider veins are there?

From a practical standpoint we distinguish two:

- Reticular veins (the “thicker” ones—still under 2 mm), usually blue-green in colour.

- Telangiectasias (very fine, hair-thin, wine-red lines).

Both types may coexist in one area—for example, a tree-like pattern where a reticular vein “feeds” smaller telangiectasias—or they may appear separately. Despite the different look, their behaviour is similar, though treatment differs.

Are they related to varicose veins?

Generally NO. Varicose veins are larger veins arising from the superficial venous system, located beneath the skin. Spider veins arise from skin capillaries, i.e., within the skin. They are different vessels in different locations.

Having varicose veins does not predispose you to spider veins, and having spider veins does not mean varicose veins will appear.

The only practical link is treatment order when both are present in the same limb and you wish to treat them: always go from larger to smaller vessels—varicose veins first, then reticular veins, and finally telangiectasias.

Why? Because all veins and capillaries are connected. Dilated veins (varicose veins) raise venous pressure across the network. Trying to close tiny capillaries while upstream pressure remains high, lowers the chance of success, increases the chance of recurrence, and can raise the risk of certain adverse effects (e.g., phlebitis, thrombosis, skin pigmentation).

What are the consequences of having spider veins?

There’s a lot of dubious or misleading information out there. Key facts:

- Spider veins NEVER cause symptoms: no pain, heaviness, or oedema. They’re simply too small to do so—even if they seem painful. If symptoms are present, look for another cause (true venous insufficiency, muscular issues, sciatica, bone/joint problems, etc.).

- Spider veins NEVER grow into varicose veins. They are different vessels in different locations; they can’t enlarge and “move” to become varicose veins.

- Spider veins NEVER cause health complications or pose a danger. The rare exception is a prominent 2 mm reticular vein connected to a high-pressure varicose vein that protrudes; a knock might make it bleed, but this is minor and resolves with compression.

So what’s the problem? Cosmetic only. They’re unsightly—nothing more.

SCLEROTHERAPY FOR SPIDER VEINS

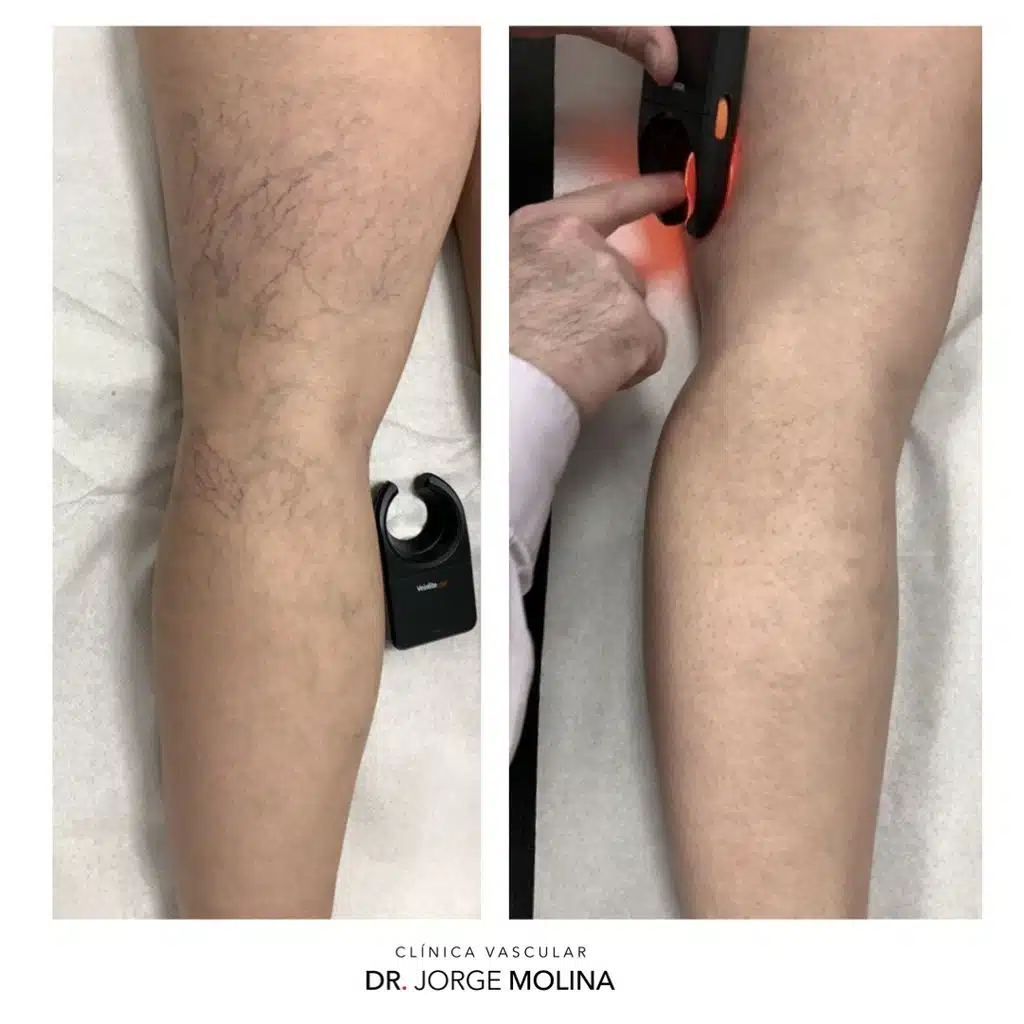

We distinguished reticular veins (thicker, <2 mm, blue-green) and telangiectasias (very fine, wine-red). Reticular veins can be safely and effectively removed with sclerotherapy. Telangiectasias, being much finer (sometimes thinner than the injection needle), may be treated with laser—ideally after finishing sclerotherapy. (Laser is beyond this article’s scope.)

Sclerotherapy involves injecting an irritant medication into the reticular vein and then applying external compression (compression stockings) to close it. Proper compression significantly improves success and reduces side-effects.

The injection should be virtually painless (no worse than a mosquito bite). If it hurts, tell your doctor immediately— the injection may be in the wrong place.

Common agents include Polidocanol, Sodium Tetradecyl Sulphate (STS), and Chromated Glycerin; the first is most used in Spain. We use Polidocanol for its favourable balance of efficacy, injection comfort, and side-effects.

The drug damages the inner lining (endothelium) by a detergent effect. Over days to weeks—and aided by compression—the mild inflammation leads the body to “stick” the vein walls together via fibrosis (a micro-scar), making the treated vein disappear from view.

We want the vein to close empty, without blood inside (compression helps). If it closes with trapped blood, the body will clear it, but this can leave ochre skin pigmentation from iron deposits (from red cells)—much like a tattoo, which is why such marks can take a very long time to fade (and may not fully disappear). Hence the importance of correct compression.

Results are generally good at removing treated reticular veins (outcomes vary with drug choice, adherence to compression, operator experience, and patient factors). Sometimes more than one injection is needed.

Side effects are usually minor but should be discussed with your doctor, as they vary with the agent used. The most concerning potential reaction is allergy, present with any medicine (thankfully rare with polidocanol; usually mild hives/itch settling within hours or days; severe reactions are very rare). Most other adverse effects are cosmetic, with skin pigmentation the most relevant (covered below).

A particular adverse effect is matting: the appearance of very tiny, short telangiectasias (1–2 mm) around the treated vein due to local inflammation. It’s uncommon and often improves spontaneously over months; laser can be used if needed.

SCLEROTHERAPY IN PRACTICE

Yes, the theory is fine—but what does it mean practically?

Sclerotherapy is performed in sessions because a drug is injected into a vein, and every drug has a maximum safe dose—especially intravenously.

A commonly accepted upper limit for Polidocanol is one 2 ml ampoule per 24 hours.

We perform treatment using polidocanol microfoam: the liquid drug is mixed with air to form a fine foam (“meringue”), which is injected. We do this for two reasons:

- Microfoam is much stronger than liquid at closing veins, so we can successfully treat larger veins with less drug (and fewer side-effects).

- The same 2 ml of drug become ~7–8 ml of foam, allowing a wider area to be treated per session (fewer sessions overall—more convenient and cost-effective).

Note: the amount of air injected intravenously is also limited for safety. So both drug dose and air impose boundaries.

If everything can’t be treated in one session, when is the next? Since the limit is per 24 hours, we can repeat after 24 h (treating a different area).

IMPORTANT: results are NOT immediate. They become assessable 4–6 weeks after treatment. We usually review at 6–8 weeks to decide if the outcome is final or whether a touch-up is advisable.

To avoid dragging treatment out, if more than one session is needed we advise to undergo as many sessions as needed to complete both legs as close together as feasible. Then both legs progress through the same 6–8 week window and can be reviewed together.

How many sessions will I need? I don’t know. It depends on how many veins must be treated, how they respond (which varies between people—and even between days in the same person), and how you feel about the result. We don’t sell “packs”; we treat patients. You decide whether to continue based on progress.

A VERY IMPORTANT DETAIL: in the weeks between treatment and review, treated veins change colour—red, purple; bruises may appear and then resolve. This is normal and irrelevant. What matters is the result at 6–8 weeks.

Sometimes a treated vein becomes temporarily more visible and firmer to the touch. Don’t worry: this means the vein closed with a small trapped clot rather than empty. It isn’t dangerous, but it takes longer to resolve (instead of 4–6 weeks, 3–4 months or more) and the risk of pigmentation is a bit higher.

Whether veins close empty (ideal) or with a small clot depends largely on strict use of compression stockings and avoiding exertion/sport in the first days (walking is mandatory). Even when doing everything right, it can still happen. If it does, the only solution is patience until the body clears it.

At the end of each session—before you get off the couch—we fit a compression stocking, to be worn for ~3 weeks (we prescribe the exact brand/model to avoid errors). Compression improves efficacy and, above all, reduces the likelihood and severity of adverse effects. It’s essential—we do not perform treatment without compression.

WHAT ARE THE SIDE EFFECTS OF SCLEROTHERAPY?

The big question!

Does sclerotherapy have side effects? Yes. As my pharmacology professor said: “Even a glass of water has side effects”—people can choke on water.

When performed correctly by an experienced professional, sclerotherapy is considered safe and low-risk, yet side effects/complications can occur:

- Allergy to the drug (as with any medicine). Polidocanol allergy is uncommon (much rarer than, e.g., penicillin or metamizole) and usually mild (hives/itch). Severe reactions are very rare.

- Skin pigmentation: the most frequent side effect (see dedicated section below).

- Matting: tiny telangiectasias around the treated vein (explained above).

- Skin necrosis or even subcutaneous necrosis: extremely rare when technique is correct; risk increases if performed by non-experts.

- Phlebitis (clot in a superficial vein): uncommon with good technique, correct stocking use, and an active lifestyle; not dangerous but can be painful—see your doctor for prompt treatment.

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): far rarer when the technique is correct (hence the need for prior duplex ultrasound and an experienced operator). Proper compression, walking and activity are very protective.

Most risks relate to poor technique (this is why your doctor’s experience matters, as do “no-go” areas and prior assessment). The most frequent side effect—PIGMENTATION—is unpredictable and can occur even when everything is done perfectly by both doctor and patient.

POST-SCLEROTHERAPY PIGMENTATION

This is a brown-ochre skin stain following the path of one or more treated veins. Sometimes faint; sometimes quite visible—even after the vein itself has been fully reabsorbed.

Pigmentation seems influenced by genetic factors, so it’s only predictable if it has happened before, or if bruises in that person tend not to clear fully (a similar biochemical mechanism involving incomplete breakdown of haemoglobin). A personal history of pigmented scars may also suggest higher risk. Always tell your doctor beforehand.

Sun exposure strongly influences pigmentation risk—hence the recommendation not to treat in summer. Moreover, two points:

- Sunlight can pass through thin summer fabrics (linen, light cotton), so clothing may not protect treated areas.

- There may be a hormonal component (e.g., MSH and melatonin) tied to longer daylight hours that increases melanin production and predisposes to pigmentation—even without direct sun on the legs.

Practically, we advise keeping legs covered (no shorts outdoors) for TWO MONTHS after sclerotherapy. For our latitude, we generally finish these treatments by mid-April (to avoid sun until mid-June) and resume towards late September.

If you’re travelling to tropical destinations during our autumn/winter where you’ll have sun exposure, remember we should not treat in the two months before the trip.

Can pigmentation be prevented?

Often, no—even with perfect technique and adherence, it can occur. But two things significantly reduce risk:

- Avoid sun exposure and avoid treatment in or just before summer.

- Strict use of compression stockings exactly as prescribed. We fit the stocking at the end of the session and recommend keeping it on for the first 24+ hours (until bedtime the next day). Thereafter: put it on before getting out of bed, wear it all day, and remove it at bedtime for 3 weeks (briefly removing only for showering).

Used correctly, compression protects against most side effects and reduces (though doesn’t eliminate) pigmentation risk.

Key takeaway: NO SPECIFIC COSMETIC RESULT CAN BE GUARANTEED, and THERE IS NO GUARANTEE THAT POST-SCLEROTHERAPY PIGMENTATION WILL NOT APPEAR. If you choose to proceed with this treatment, we’ll do everything possible to minimise this probability, but you must assume the possibility of it happening regardless, at your own risk.

And if pigmentation appears?

Despite the warnings, most pigmentations fade on their own—with time.

Roughly 80% of cases improve spontaneously (fully or partially) within 1 year. That means up to 20% may persist beyond a year and can be considered “permanent”.

If pigmentation appears, avoid sun exposure and use SPF 50+ sunscreen; pigmented areas tend to tan even more readily, which can fix the colour.

Can pigmentation be removed?

Yes. Intense Pulsed Light (IPL/VPL), in expert hands, can give very good results for post-sclerotherapy pigmentation. We reserve it as a last resort when a reasonable time has passed and spontaneous fading has not occurred.

SPECIAL PRECAUTIONS

Although sclerotherapy is generally simple and low-risk, there are situations requiring special caution (or where it should not be done):

- Pregnancy. Safety of these drugs for the foetus is not established, so avoid them. Pregnancy often brings new veins/spider veins that may partly resolve after delivery, so treatment would be pointless. As this is a cosmetic procedure, it can and should be deferred. If you might be pregnant, tell your doctor and cancel treatment.

- Breastfeeding. Similarly, it’s unclear whether these drugs pass into breast milk; as an elective cosmetic treatment, postpone it. If you’re breastfeeding, inform your doctor to cancel treatment.

- Flights. As with all vein procedures, avoid flying for 15 days after treatment due to an increased risk of venous thrombosis. If you have a flight booked, please tell us so we can reschedule your treatment.

- Immobility. Effective, safe sclerotherapy requires that you can walk and mobilise normally. Reduced mobility or immobilisation (e.g., cast/splint) increases the risk of complications (especially phlebitis/DVT), so treatment is discouraged.

- Hormonal therapies (contraception, HRT, some oncology regimens). These treatments tend to promote spider veins, making cosmetic efforts less durable. Emerging evidence also suggests a higher risk of serious adverse events (phlebitis/DVT) when sclerotherapy is performed while on such therapies; international phlebology guidelines increasingly recommend withdrawing them before sclerotherapy.

- Age. Many risks rise with age. For sclerotherapy, the risks of phlebitis and DVT clearly increase with age. From around 65–70 years, your doctor should assess the risk–benefit balance individually.

Should you be interested in getting to know this disease better, and its causes, consequences, how to treat them, and, even better, what can we do to prevent them, you can find it all well explained in the ebook VARICOSE VEINS: Truth & myths.